Introduction

Rachel Reeves’ flagship National Wealth Fund is under the microscope, and not for the reasons she’d hoped. A recent audit has flagged “weaknesses” in the £27.8bn fund’s risk controls, raising eyebrows about whether the body’s internal systems can keep pace with its rapid expansion. With 62% of its loan portfolio sitting in high-risk territory and annual losses climbing, questions are mounting: Is this Labour’s bold growth engine or a governance headache waiting to happen?

What the Audit Actually Found

The National Wealth Fund’s internal audit pulled no punches. Auditors gave the fund a “limited” rating, essentially a yellow card in governance speak. The main culprit? Outdated systems struggling to handle the fund’s explosive growth.

Key Problem Areas

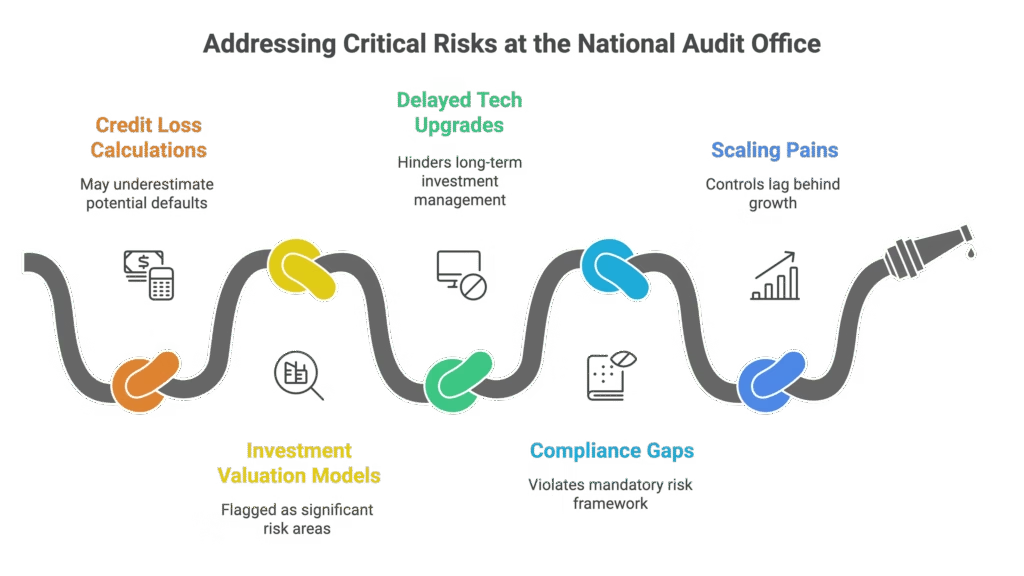

Five specific risks jumped out to the National Audit Office:

- Credit loss calculations that might not capture the full picture of potential defaults

- Investment valuation models flagged as “areas of significant risk”

- Delayed tech upgrades to a proper long-term investment management system

- Compliance gaps with the government’s mandatory “orange book” risk framework

- Growing pains as the organisation scales faster than its controls can adapt

The good news? No material misstatements were found. The bad news? That’s a pretty low bar.

Why the Fund’s Risk Profile Is Raising Eyebrows

Here’s the thing: the National Wealth Fund is supposed to be risky. That’s literally the point. It’s designed to back projects that private investors won’t touch with a bargepole.

But 62% of the fund’s private sector loans carry B+ ratings or worse, that’s deep into junk bond territory. For context, these are the kind of assets that make traditional bankers break out in hives.

The Price Tag of Ambition

The fund’s losses tell their own story:

- 2023-24 losses: £152.2m before tax

- Previous year: £85.6m

- The verdict: Expected, but higher than budgeted due to “specific challenges” in digital infrastructure

NWF bosses say losses are part of the plan at this growth stage. The Treasury Committee isn’t entirely convinced, with chair Meg Hillier noting MPs “remain to be convinced” the fund will “meaningfully shift the dial on economic growth.”

From UKIB to NWF: A Costly Rebrand

Remember the UK Infrastructure Bank? Neither does anyone else, because it’s now the National Wealth Fund. Chancellor Reeves announced the rebrand in October 2024, expanding the remit to £27.8bn in public capital.

The transformation wasn’t cheap. The rebrand alone cost nearly £90,000, sparking criticism that calling it a “wealth fund” is misleading compared to actual sovereign wealth funds (which are typically funded by oil money or foreign currency reserves, not taxpayer borrowing).

The Leadership Premium

Running a high-risk public fund comes with serious compensation. Former CEO John Flint pocketed £555,000 annually, a figure that’s bound to attract scrutiny when losses are piling up.

What Happens Next?

The fund’s board maintains that internal controls “continued to be effective” and insists they’re on track for profitability within this Parliament. Their defence? They’re identifying risks early and taking action, which is precisely what you’d expect them to say.

Former City minister John Glen summarised the challenge neatly: “Since the NWF is not a conventional sovereign wealth fund—financed by borrowing and taxes rather than foreign currency reserves—it has a greater duty to be administratively prudent.”

Translation: When you’re playing with taxpayer money, you can’t afford sloppy controls.

Conclusion

The National Wealth Fund’s audit reveals a classic scaling problem: big ambitions running ahead of the systems meant to keep them in check. While some losses are inevitable with high-risk investing, the control weaknesses suggest the fund needs to tighten up its governance before the stakes get even higher. Whether it becomes Labour’s growth success story or a cautionary tale about moving too fast will depend on how quickly those fixes happen.

Want to understand how government investment vehicles work? Check out our guides on sovereign wealth funds and public sector lending.

FAQ

Q1: What is the National Wealth Fund?

A: The National Wealth Fund is the UK government’s £27.8bn investment vehicle designed to back high-risk projects that private investors typically avoid. It was created in October 2024 by transforming the UK Infrastructure Bank, with a mandate to drive economic growth through ambitious investments.

Q2: Why did the audit flag the National Wealth Fund?

A: The audit identified weaknesses in risk management, internal controls, and governance systems that haven’t kept pace with the fund’s rapid expansion. Specific concerns included outdated investment management systems, gaps in compliance with mandatory government risk frameworks, and potential issues with how it calculates credit losses and values investments.

Q3: Are the National Wealth Fund’s losses a problem?

A: Not necessarily, losses are expected when investing in high-risk projects that private markets won’t touch. The fund’s £152.2m loss was higher than budgeted due to challenges in digital infrastructure, but officials say profitability should arrive within this Parliament. The bigger question is whether the control weaknesses might lead to preventable losses down the line.

Q4: How is the National Wealth Fund different from sovereign wealth funds?

A: Unlike traditional sovereign wealth funds (funded by oil revenues or foreign currency reserves), the NWF is financed through government borrowing and taxes. This means it faces higher scrutiny and has “a greater duty to be administratively prudent” with taxpayer money, according to former City minister John Glen.

Q5: What percentage of the fund’s portfolio is high-risk?

A: Nearly 62% of the National Wealth Fund’s private sector loan portfolio carries B+ ratings or lower, considered high-risk or “junk” territory in credit markets. This reflects the fund’s mandate to back ambitious projects that traditional lenders typically reject, though it also explains why losses are mounting.

DISCLAIMER

Effective Date: 15th July 2025

The information provided on this website is for informational and educational purposes only and reflects the personal opinions of the author(s). It is not intended as financial, investment, tax, or legal advice.

We are not certified financial advisers. None of the content on this website constitutes a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any financial product, asset, or service. You should not rely on any information provided here to make financial decisions.

We strongly recommend that you:

- Conduct your own research and due diligence

- Consult with a qualified financial adviser or professional before making any investment or financial decisions

While we strive to ensure that all information is accurate and up to date, we make no guarantees about the completeness, reliability, or suitability of any content on this site.

By using this website, you acknowledge and agree that we are not responsible for any financial loss, damage, or decisions made based on the content presented.