Rachel Reeves just delivered a Budget that’s pulling almost a million people into the 40% tax bracket. If you’re earning a decent salary and wondering why your take-home pay feels squeezed, you’re not imagining it.

The Chancellor froze income tax thresholds again, which sounds boring until you realise it’s an £8bn stealth tax. As wages rise with inflation but thresholds stay frozen, more people slide into higher brackets without technically seeing a “tax rise”. Clever? Sure. Popular? Not so much.

With £26bn in extra revenue targeted by the end of parliament, this Budget is setting records—and not the good kind. Let’s break down what’s actually happening to your wallet.

The Numbers Don’t Lie: Who’s Paying More?

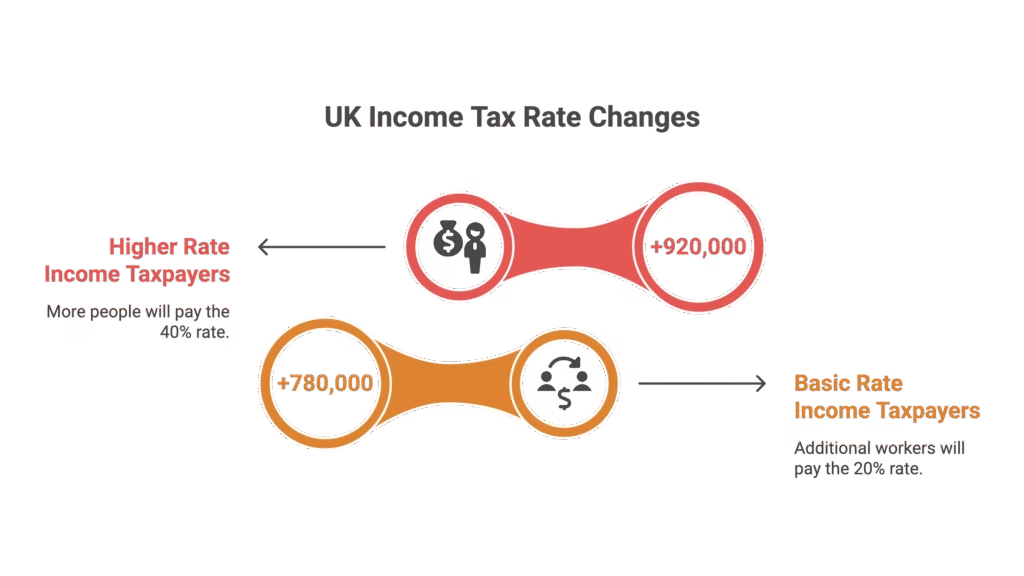

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), here’s the damage:

- 920,000 more people will pay the 40% higher rate on their income

- 780,000 additional workers will start paying the basic 20% rate

- £8bn total extracted through frozen thresholds alone

This threshold freeze was supposed to be temporary. It’s now looking pretty permanent.

The kicker? Labour promised not to hike taxes on working people during the election campaign. Economists and opposition parties are calling this exactly that—just dressed up in different clothes.

Why Reeves Needed the Cash (Spoiler: It’s Expensive)

The Chancellor didn’t freeze thresholds for fun. She’s dealing with some serious budget black holes:

A £16bn productivity downgrade means the economy isn’t growing as fast as hoped. Less growth equals less tax revenue without raising rates.

Then there’s the £73bn welfare spending splurge over five years. That money needs to come from somewhere, and Reeves chose your payslip.

The wealthy, motorists, and savers are also getting hit with tax increases. But the threshold freeze affects the middle class most—people earning £50,000 to £100,000 who suddenly find themselves in “higher earner” territory.

The “Spend Now, Pay Later” Problem

Most of the tax hikes are back-loaded, meaning they kick in closer to the next General Election.

Helen Miller from the Institute for Fiscal Studies called it a “spend now, pay later” Budget with “no real appetite for using tax reform to boost growth”. Translation: quick fixes now, bigger problems later.

Top City analysts aren’t buying it either:

- David Rees from Schroders (a major government bond holder) reckons more tax hikes or spending cuts are coming soon

- Andrew Goodwin from Oxford Economics says the package lacks credibility due to “backloaded measures” and “absence of growth measures”

The OBR gives Reeves just a 59% chance of meeting her own fiscal rules. That’s barely better than a coin flip.

Her fiscal headroom—the budget cushion she needs to hit targets—more than doubled to £22bn. That sounds comfortable until you realise how easily economic forecasts can shift.

Political Fallout: Everyone’s Taking Shots

Opposition leaders aren’t holding back:

Kemi Badenoch (Conservative leader) called it a “laundry list of excuses” and demanded Reeves’ resignation for “breaking promises”.

Nigel Farage (Reform UK) labelled the Budget an “assault on aspiration”—and for once, middle-class workers earning £60k might agree with him.

Even Reeves herself sounded uncertain. When asked if she wanted to deliver this Budget, she admitted: “I would have rather the circumstances were different.”

That’s not exactly a ringing endorsement of your own policy.

What This Means for Your Money

If you’re earning between £50,271 and £125,140, you’re in the firing line. Every pay rise pushes more of your income into the 40% bracket whilst thresholds stay frozen.

Someone earning £55,000 today will pay significantly more tax in two years—not because rates increased, but because the goalposts didn’t move with inflation.

This is fiscal drag in action: a stealth tax that feels like death by a thousand cuts rather than one big headline-grabbing increase.

The bigger worry? If this Budget is “spend now, pay later”, what happens when “later” arrives? More tax hikes? Spending cuts? Both?

The Bottom Line

Rachel Reeves delivered the UK’s highest-ever tax burden whilst technically keeping Labour’s promise not to raise income tax rates. The frozen thresholds do the heavy lifting instead.

Nearly a million more people will pay higher-rate tax. The public finances look shaky. Growth measures are thin on the ground.

If you’re planning your finances for the next few years, factor in less take-home pay and potentially more tax changes ahead. This Budget might be done, but the pain is only just beginning.

Want to reduce your tax bill? Check if you’re maximising pension contributions and ISA allowances, they’re some of the few legal ways to keep more of your money.

FAQ: Your Budget Questions Answered

Q1: Will income tax rates increase in the future?

A: Reeves didn’t rule out future tax changes, saying she “can’t write future Budgets”. Given the tight fiscal situation and low probability of meeting targets, further increases or spending cuts are likely within the next few years.

Q2: What does “fiscal drag” actually mean?

A: Fiscal drag happens when tax thresholds stay frozen whilst wages rise with inflation. You earn more in nominal terms, but more of your income gets taxed at higher rates. It’s a stealth tax that increases government revenue without technically raising tax rates.

Q3: How likely is Reeves to meet her fiscal rules?

A: The OBR gives her just a 59% chance—only marginally better than the Spring Statement. With £22bn headroom and back-loaded measures, most economists think she’ll need further consolidation (tax rises or spending cuts) before the next election.

Q4: Who gets hit hardest by frozen tax thresholds?

A: Middle-income earners between £50,000 and £100,000 feel it most. They’re dragged into the 40% bracket or see more of their income taxed at higher rates, whilst wealthier individuals already pay top rates regardless of threshold changes.

Q5: Is this Budget actually going to boost growth?

A: Probably not. The Institute for Fiscal Studies noted “no real appetite for using tax reform to boost growth”, and the £16bn productivity downgrade suggests the economy is underperforming. Most measures focus on revenue raising rather than growth generation.

DISCLAIMER

Effective Date: 15th July 2025

The information provided on this website is for informational and educational purposes only and reflects the personal opinions of the author(s). It is not intended as financial, investment, tax, or legal advice.

We are not certified financial advisers. None of the content on this website constitutes a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any financial product, asset, or service. You should not rely on any information provided here to make financial decisions.

We strongly recommend that you:

- Conduct your own research and due diligence

- Consult with a qualified financial adviser or professional before making any investment or financial decisions

While we strive to ensure that all information is accurate and up to date, we make no guarantees about the completeness, reliability, or suitability of any content on this site.

By using this website, you acknowledge and agree that we are not responsible for any financial loss, damage, or decisions made based on the content presented.